Home » Simple on the Surface, Complex Underneath: Lessons from a Real-World Trial

Simple on the Surface, Complex Underneath: Lessons from a Real-World Trial

July 29, 2019

Trying to make a real-world data study as easy as possible for practitioners and participants requires a great deal of work behind the scenes, experts say, but careful planning pays off.

Representatives of GlaxoSmith Kline’s Salford Lung Study (SLS) say there are unique challenges in conducting a trial that brings together both clinical research and real-world data.

The benefit of such hybrid studies is their ability to answer questions about a therapy’s safety and efficacy while simultaneously collecting information about the best way to implement that therapy in a real-world setting.

The SLS, the first major drug trial conducted under “real world” conditions, evaluated GSK’s Relvar among 4,233 patients with asthma and 2,802 patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The studies were designed as open-label, Phase 3, randomized trials.

The goal of the trial was to show the benefit of a once-daily administered drug, says Elaine Irving, senior director and head of real-world study delivery at GSK, which can’t be done in a blinded scenario. GSK focused the trial on practical endpoints that physicians use in day-to-day practice, Irving says, and tried to keep the patients as close to routine care as possible. Active randomization helped maintain scientific rigor.

The first lesson learned, Irving points out, was how many moving parts such a seemingly simple study can have. “The simpler we make the concept,” she says, “the more complicated it is behind the scenes and the longer it takes to get one of these studies actually started.”

“I think this study took four years of discussion and planning before we hit the first subject to be recruited.” The sheer numbers of stakeholders in the asthma study alone — 74 physician practices, 132 community pharmacies, 165 trainers and facilitators and 4,233 patients — meant determining everyone’s needs was heavy lifting.

But buy-in is essential, Irving says. “These types of studies can’t be done unless you have a partnership with all the different parties.” For the SLS, this meant reaching into all corners of the community in Salford and South Manchester, England, to gather local hospitals, primary care doctors, academic experts and health informatics specialists. In addition, SLS coordinators kept national regulators up to date.

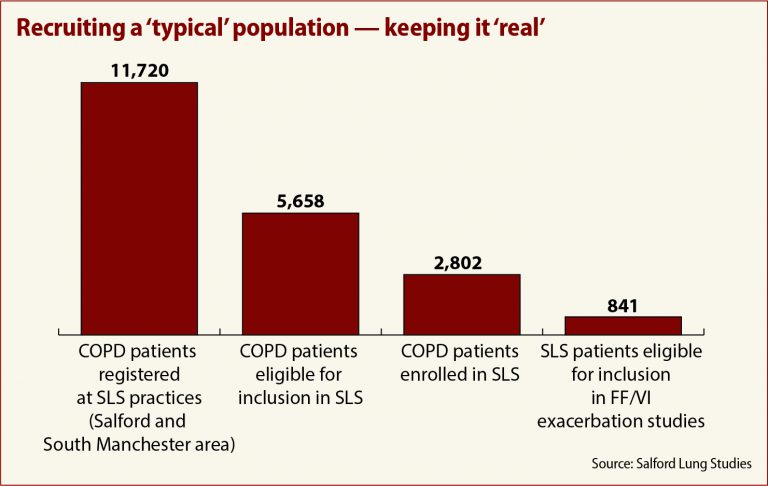

And keeping eligibility standards broad resulted in a more representative study population. Instead of employing traditionally rigid clinical trial inclusion criteria, the SLS tried to reach out to everyone in the community with asthma and COPD, even smokers and people with other comorbid conditions.

In the COPD study, 11,720 patients registered to participate at their local doctor’s office, 5,658 were found to be eligible, and 2,802 — 50 percent — were enrolled, a far cry from the 841 patients who would have qualified under more traditional clinical trial standards.

Support for the physicians involved also was a key factor. Trial designers wanted to place as little burden on them as possible. “If we had the design right,” Irving says, “we were asking [them] to do their jobs. We weren’t asking much else.” The SLS provided nurse support teams to take on extra tasks related to the trial, such as identifying patients, conducting study visits and data entry.

Training also was a necessary component. These were research-naïve medical professionals, Irving points out, who needed education in good clinical practices and trial procedures. Local pharmacies also needed training in handling investigational drugs and good manufacturing practices.

It was also important to make the study team as diverse as possible, Irving says, combining clinical statisticians used to working only with eCRF data with epidemiologists who specialize in real-world practice. “That involves bringing two completely different worlds together,” she says.

Using real-world data also requires a change in mindset, Irving stresses. Data was collected from patients only when it didn’t interfere with their regular care, and then only when the data added value to the study.

Outcomes and safety data were collected from the electronic record systems at general practices and pharmacies. That presented a challenge all its own, according to Martin Gibson, University of Manchester professor and head of the team that created the technology behind the study.

When it comes to electronic data records, “standards are like toothbrushes — everyone’s got one, but nobody wants to share,” Gibson says. And varied data sources in an RWD study make standardizing difficult. They may have different coding systems, data may be duplicated, sources may be difficult to query.

In a real-world study, it’s necessary to either build or buy “a system that brings all those different data standards together,” he says.

The outcome of GSK’s efforts ultimately was positive. The SLS demonstrated not only that Relvar was safe and effective, but also that it improved patient outcomes in a real-world setting, a factor that may strengthen the drug’s position among payers.